- A new phase of the US immunization campaign has begun, with supply now expected to exceed demand.

- Public-health experts are debating whether vaccine mandates for some groups would help or hurt.

- Some organizations, like a major Houston health system, are requiring the shot for their employees.

- See more stories on Insider's business page.

The US vaccination campaign is entering a new phase, marked by excess supply of shots. And public-health experts, bioethicists, and doctors are debating whether or not mandating the COVID-19 vaccine would be helpful or harmful.

The arguments for and against mandates are shaping up to be a signature element of this next phase of the immunization campaign, as the key challenge in reaching herd immunity shifts from supply to demand. And experts are split on whether or not it's time to start enacting such requirements, as much of the nation continues to re-open and relax public-health restrictions.

Amid the debate, a small smattering of businesses and organizations are already requiring the shot, including a New York restaurant, a factory in Louisville, Kentucky, and a large health system in Houston. More than 100 colleges and universities have said they will require the shot for students and staff to return to campuses in the fall.

Overall, in conversations with five bioethicists, doctors, and public-health experts, Insider found an array of opinions on mandates. The most ardent backers say they should be rolled out now. Other supporters say they make sense in the next few months. Other experts warned the mandates are a heavy-handed approach that will be harmful at this stage in the rollout. There should be more in education and outreach to hesitant groups before requiring the shot, they say.

Art Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University, said he hopes more groups will follow the mandate track.

"Why are we still battling vaccine hesitancy with one hand behind our back?" Caplan told Insider. "Let's start to move a mandate through populations that are posing risks to others."

Caplan and other experts in favor of mandates aren't talking about requiring the general public to be immunized. Instead, he said specific groups of people should be required to get the shot. His list includes healthcare workers, nursing home staff, military, people in congregate living settings like college dorms or group homes, customs and immigration workers, and people working in prisons or jails. Many of these groups were among the first to be offered the shot.

Jeff Fusco/WireImage

To do this, Caplan wants action at multiple levels, including the federal government, state governments, and private organizations. For example, a state legislature could insist its state police force be immunized. A private hospital could adopt a policy on its own, similar to the way many healthcare organizations require the flu shot.

In Caplan's view, mandates would help maintain the pace of vaccination, which has fallen dramatically over the past few weeks.

The rate of adults in the US getting their first dose peaked in early April at nearly 2 million per day. Now, that pace has dropped by nearly 50%, to about 1.1 million daily.

About 55% of adults in the US have received at least one dose, with 38% fully immunized, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People on the fence about the shot would be nudged to roll up their sleeve. Ultimately, mandates would leave the US better prepared against the threat of another wave of illnesses and deaths, Caplan says.

Not all experts agree. Dr. Tia Powell, director of the Montefiore-Einstein Center for Bioethics, told Insider that mandates are the wrong strategy and will be harmful.

"It's expedient. It feels efficient," Powell said. "But I think it's really shooting yourself in the foot in the long run, particularly for any matter dealing with public health."

"The lack of trust in medicine and government is a critical issue right now," she added. "This will really light that problem on fire if you're forcing people to take the vaccine who are uncomfortable and frightened about it at the expense of losing their job."

As the unsettled debate heats up, some businesses and organizations are already rolling out requirements, tethering employment to someone's vaccination status. Job postings ranging from a sommelier at an upscale restaurant in New York to an assistant at the Boys & Girls Clubs in San Francisco are requiring vaccination, The Wall Street Journal's Chip Cutter reported.

Mandates could also skirt around some of the more troubling concerns around the idea of so-called vaccine passports, or digital apps that could allow businesses -like a theater, sports stadium, or concert hall - to verify the vaccination status of their customers. Vaccine passports have become a heavily politicized topic, with critics arguing it is an invasion of privacy and allows people to be tracked. Mandates, unlike passports, would likely be a one-time verification with an employer or specific organization.

Mandates face many challenges, but there is precedent

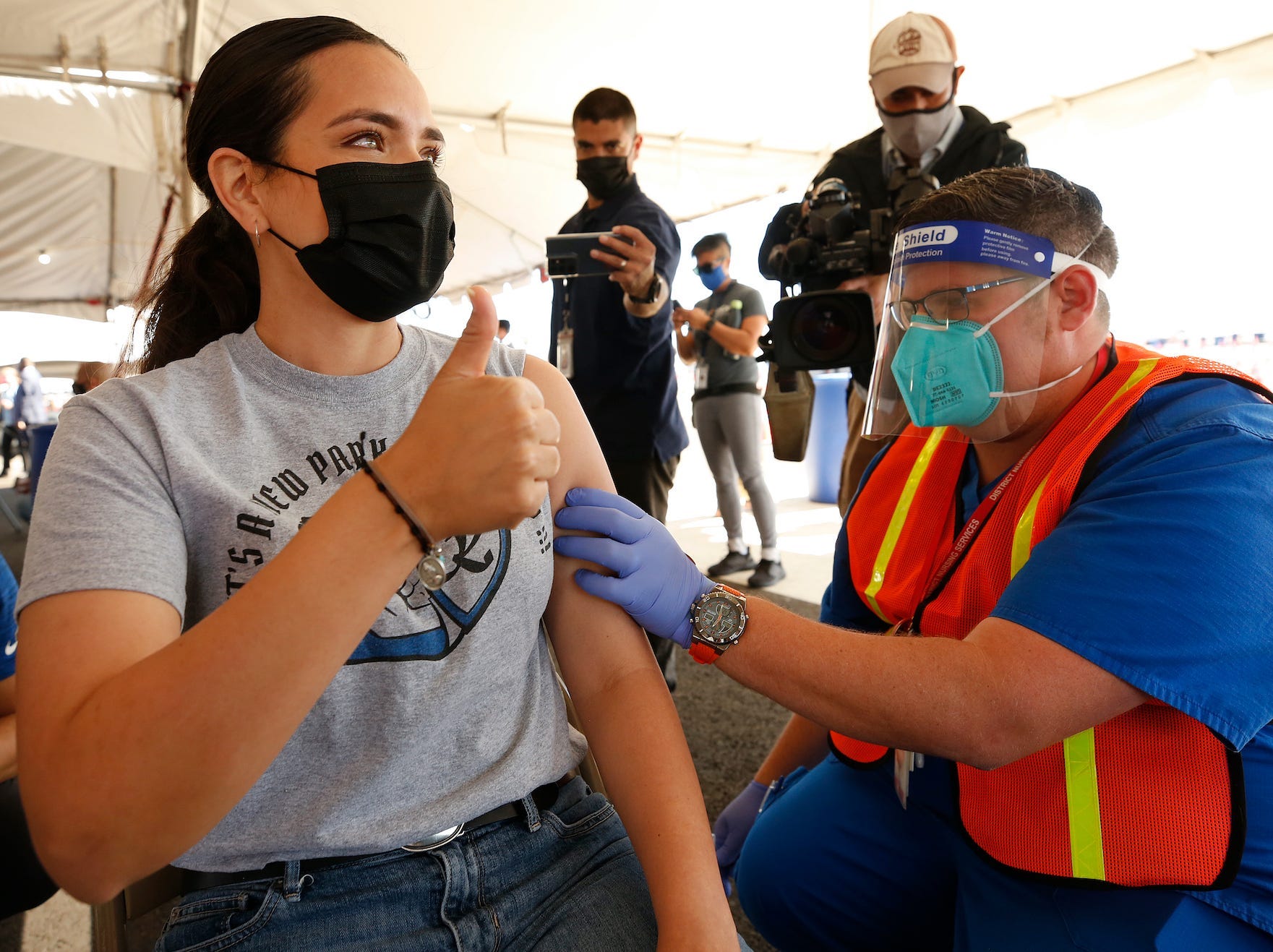

Al Seib / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Mandates face an array of legal, ethical, and logistical challenges.

Experts widely anticipate that a mandate will eventually wind up in court, challenged by a civil-rights or libertarian group. Advocates like Caplan and Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of University of California, San Francisco's medical school, said they're confident mandates would legally prevail.

In general, employers can require vaccination, providing some exemptions for medical and religious reasons. Mandates aren't unheard of. Many healthcare systems require the flu shot. Basic vaccinations, like against measles, are required for children in many states to attend school or daycare. Even then, these mandates aren't foolproof and have brought controversy. Small-scale measles outbreaks have still happened recently in the US. Parents can typically claim a range of religious or medical exemptions to avoid the requirement for their children.

A common argument against enacting mandates now is the COVID-19 vaccines are not fully approved medicines. US regulators issued emergency use authorizations for the shots developed by Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and Johnson & Johnson. An EUA provides regulators with more flexibility during a crisis than the standard pathway of approval.

"If it is fully approved, I'm a lot more comfortable with it," said Andrew Noymer, an associate professor in population health and disease prevention at University of California, Irvine.

For now, Noymer said groups should be doing more educational work to convince hesitant people.

"I think mandates are for when you've exhausted all approaches that make people feel like stakeholders," Noymer said. "It's heavy-handed, and I think we need to exhaust all avenues of encouragement before we go to mandates."

Caplan and Wachter don't buy the argument on waiting for full approval. Both experts rebuffed the notion that these vaccines should be treated like experimental medicines, citing the fact that more than 140 million Americans have already gotten at least one dose.

"If you're not sure that it should be out there, then what are we doing?" Caplan said. "Of course we're sure this is a safe and good thing to do: we're vaccinating millions."

Waiting until full approval is a "quasi-argument," Wachter said, given the results from the rollout show these vaccines to be extremely safe and protective.

"The evidence on the vaccines after having been administered to more than 100 million people in the United States, the evidence is as clear as it's going to be that they are breathtakingly effective," Wachter said.

Some experts also see ethical challenges for mandates today. Powell, the bioethicist in New York, said such requirements needlessly lean on the force of authority, threatening to further politicize public health.

"We haven't earned the right to come in and enforce," she said. "It's lazy and it's arrogant and I don't think we should do that."

Stefanie Friedhoff, a professor of the practice in health services, policy, and practice at Brown University School of Public Health, said ""there's absolutely a role for mandates to play."

But she also said that how they are rolled out and communicated with the public is crucial in gaining support. In particular, she said people should still have time to make the decision. Forcing them into vaccination may stoke distrust, particularly among people of color who have a deservedly rocky history in trusting the medical system.

"In the long run, we need the mandates. They are important and they get people over the hill," Friedhoff said. "But in this current moment, we have these overlapping issues and it's not just the EUA. It includes the overall respect for some people will take a little bit of time to get to that decision and to give them the chance to trust the healthcare system in new ways. That's where I think a mandate has the potential to backfire."

Ultimately, even for proponents of mandates, the logistical hurdles are daunting. There's no federal system to authenticate that someone has gotten a vaccine. People get paper cards from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention after getting the shot, but those can be easily forged. Scammers already sell fake cards online. A mandate would be tough to enforce if it's difficult to validate someone's vaccination status.

"To me, I don't think the legal issues are problematic. I don't find the ethical issues particularly problematic now that vaccine is available for everyone," said Wachter. "Right now, it's mainly a matter of can we come up with a trustworthy system. We should have started on it six months ago, but we didn't, so now we got to scramble."

If those logistics can be figured out, Wachter said vaccination mandates will be close to a no-brainer for many employers and organizations.

"By and large, the benefits of not only moving the entire community toward herd immunity but creating a workplace where everyone feels that it is safe to be there far outweigh the downsides," he said.

Mandates are being trotted out. Will more follow?

Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Even as the debate goes on, mandates are happening at some organizations, including Houston Methodist Hospital.

The 26,000-worker health system became the first major health system to require the shot so far. Every employee needs to provide proof of vaccination by June 7. Workers need to apply for medical or religious exemptions by May 3. For those that still choose not to get vaccinated and don't have an exemption, they will be suspended without pay and eventually fired.

Jennifer Bridges, a nurse at Houston Methodist, is planning to sue the hospital over the requirement. "All we're asking is: just more time," she told KHOU11, a local TV news station.

There about 3,000 employees holding out on getting the vaccine, Houston Methodist CEO Dr. Marc Boom said, defending the policy even in the face of legal threats.

"We're never going to make anybody take the vaccine," he told KHOU11. "But at the end of the day if they choose not to take the vaccine there are many other places they can work."

More health systems could follow soon. Houston's Memorial Hermann Health System is also planning on mandating the shot for workers, CNN reported on April 26. That organization has yet to set a firm deadline for getting the shot.

Wachter said he's particularly surprised that so few healthcare organizations have implemented requirements.

"I don't think it's a close call anymore," he said. "Someone working in an environment surrounded by people at high risk of getting very sick and dying have an ethical obligation to be vaccinated."

Healthcare systems may be fretting about the politics and pushback from some employees, Wachter said. It's likely a handful of workers would quit an organization over such a mandate. Still, Wachter said he's imploring healthcare systems to step up, particularly as some colleges and businesses are ahead in requiring vaccination.

One surprising element is far more colleges have said they will require vaccination than hospitals and health systems. That could lead to a bizarre dynamic this fall, UCI's Noymer said, when college kids need to get the shot but not necessarily most doctors or nurses.

"If your local state U is requiring it of their freshmen, it's a good question why your local hospital isn't requiring it of a respiratory tech or a doctor," he said. "I think things will come to a head in the fall, when you have literally dozens of colleges and universities requiring it for returning students but not your local hospital. That seems weird."

Dr. Francis Collins, the head of the National Institutes of Health, said he wouldn't disagree with private groups mandating the vaccine.

Collins said Sunday on Meet the Press that once "we no longer have this block about it being emergency use" groups could be more assertive in encouraging or requiring the shot.

For now, Collins is only encouraging, not mandating, vaccination within the NIH, he said.